CHAPTER 1

The Spanish East Indies

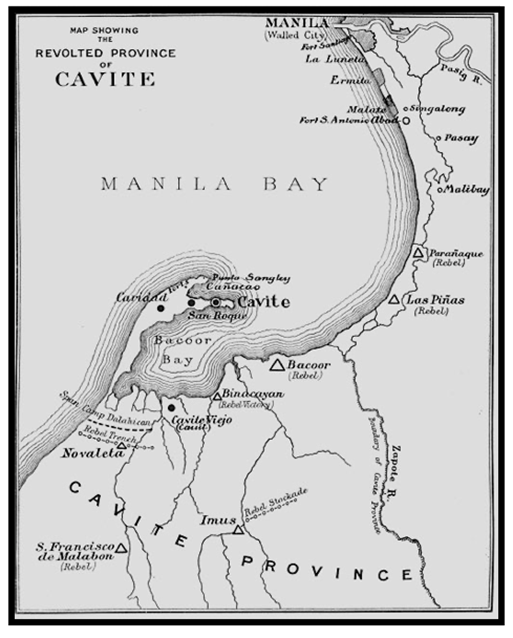

Display 1-1: Porto de Cavite, Philippines 1641.

24th of April, 1667: On those all to frequent days when there’s little or no wind, when there’s plenty of heat and humidity for all, and the skys are clear and cloudless–misery abounds. Such is the narrative of the tropics. Early mornings are often an interlude from this as they can be pleasantly cool, but today–the 24th of April 1667–the day of departure, dawn is a mere glow far to the east; …and it’s already miserable.

1

Forty minutes later, low on the eastern horizon hangs the rising sun. It tints the waters of Manila Bay a yellowish gold, and silhouetted within the confines of the bay are a dozen or more ships anchored and moored at Manila’s port of Cavite. The largest three, those of the Spanish Crown, are galleons bristling with cannon and huge, colorful flags. The others are a motley gathering of caravels1 and carracks2, except for six, which are neither. These six and the other ships belong to the port’s Spanish merchants-captains.

These merchant-captains were the “explorares” of the Spanish East Indies, agents of the Crown; and though rowdy, they were generally an honorable and courageous lot. They had to be too survive. They were the ones who sourced Manila with the wealth of the East Indies and that of China, wealth that was annually shipped eastward across the Pacific to New Spain (Mexico) and onto old Spain’s port of Cadiz.

Among these men, there is one Capitan Alfonso Bernardo Quinones

who stands out from the others, and if it is true–as the story is told–he was a man, who in our time, might be labelled an “amiable, talented opportunist of many facets.”

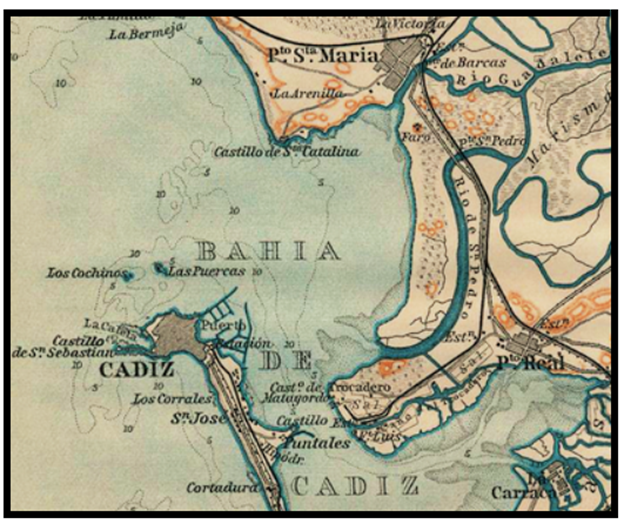

Display 1-2: Porto de Cadiz, Spain 1638.

2

Alfonso was born into moderate wealth. The year was 1618 and the Thirty Years War had just erupted. He, like others, grew-up in a time when Europe slid into another phase of religious-fueled savagery like that which followed the Black Death and the diaspora of the Jews. It was what shaped his youth and his manhood. He was driven as a lad, known to be energetic, self-disciplined, and most cunning; and also said to be good with the poleax, the blade and the pistolas. Throughout his youth he was rigorously mentored by his well connected, aristocratic father, a man of MesoAmerican-Spanish linage who was a close friend of King Philip IV’s confidant/courtier/secretary, a one Don Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke Olivares.

Olivares and King Philip IV grew close in childhood; and the former, because his intellectual inclinations, formulated most policy positions for Philip through most of his reign. Olivares, therefore, greatly influenced the kingdom’s destiny until the years of 1648 when he fell-out of favor with Philip’s other supporters and had to be dismissed. But during Alfonso’s time, he was the man to know.

Olivares met the young Alfonso at the conclusion of the later’s formal education in languages and in the discipline of mathematics. This and the energetic mannerisms of each was an attractor that drew them together in a relationship that opened possibilities for the young man, particularly for one so bright with a passion for ships. The wealth of correspondence (now lost of course) between the two was said to be a testament of Olivares’s mentoring, their financial ties, and collisions.

Having completed his studies, Alfonso wanted nothing more than a life at sea. This choice was naturally a source of aggravation with his father who saw his son’s future better served in the employ of the Crown–that is, within the realm’s lands of Iberian Spain and close to the seat of power. Though Olivares understood his father’s desires and concerns, he counseled his old friend to recognized his son’s youth, vigor, sense of adventure, and the draw of the sea.

He said, “How could such a dream be avoided for one who grew-up sailing in and around our port Cadiz, …and witnessing the comings and goings of our treasure ships? Is it not a fascination to all…, particularly to a talented young men like your son… Alfonso?”

Señor Quinones relented, and with his hand laid upon Olivares’s shoulder, he was said to say, “Yes…, your counsel is wise my friend. I must agree. It can’t be otherwise.”

Over a fine dinner sometime later, he and Olivares blessed the young man’s wishes, and provided monies for the purchase and the out-fitting of a large, sea-going vessel of Alfonso’s choosing. Accordingly,

Alfonso entered into the maritime world as a merchant captain, …a trader of goods. He was, of course, well connected and made the most of these relationships, primarily by moving bulk cargos of metals within the confines of the Mediterranean. Trade between the northern ports of Italy and Cadiz was most lucrative at first. Then he moved elsewhere, and on two occasions ventured to West Africa into the realm of the Portuguese for gold and ivory. Wherever he sailed, however, there were nefarious authorities, pirates, and thief-infested ports.

Of the sea-going villains—the pirates—he had seven encounters where his cunning and aggressive nature came to the forefront. In most instances, he preferred to out-sail the menace, but on two, he defeated them in battle and made off with their loot and lives. From the beginning, Alfonso drilled his crew to sail and fight smart, and his ship, the El Calaveras, was well armed with British cannons, German musketry, and Spanish steel and courage.

3

Three years later, in 1648 and at the conclusion of the Thirty Years War, he crossed the Pacific voyage to the Spanish East Indies. And though he held the rank of captain, he was placed second in command on a large galleon sailing from Acapulco, Mexico to the West. The ship along with others carried New Spain’s cargos of silver and other trade goods in company with a flock of Crown officials, papal delegates, and a large contingent of the faithful–God’s warriors.

Amongst the papal delegates were senior members of the Church, an archbishop (a replacement for one deceased Don de Francisco Espinoso), his staff, a fair number of lesser priests and the hardcore devotees. In addition to these, there were the sailors, a modest contingent of solders, and a handful of hope-filled colonist seeking to escape the rigors of mid-seventeenth life in their European homeland. As a result, these westward journeys had to maximize their human cargo-numbers; Spain needed to move as many as possible with each crossing, and this met stuffing the ships.

Quinones’s ship along with the others of the squadron were crowded hulks, loaded with hundreds upon hundreds in a space no more than 120 feet in length, maybe 35 feet abeam, and maybe three or more decks occupied by all sorts of non-human things, which took up living space. Next to the senior officers, the papal delegates normally received the choicer accommodations, which of course, isn’t saying much. For all concerned, the journeyed was a “close-packed affair.”

Crossing the Pacific during the centuries of imperialism was often a death sentence, as well. Starvation, scurvy along with all sorts of accidents took many. And not to be dismissed was the weather and it’s brotherhood with the seas.

The Pacific is so named as a realm of “peace and tranquility,” but as we now know, our Earth’s largest ocean is anything but peaceful. Its northern and southern extremities are terrorized by unruly weather nearly year round, and the cyclonic storms (typhoons, hurricanes and cyclones) are the scourged of the tropical midsections. As with all large bodies of water, immense storms with their massive seas are common, and among them are the giants—rogues, freak waves so large that they crush and drive ships under mountains of waters in an instant. Ships and crews swallowed by the sea: gone, crushed, or stranded on some unknown fragment of terra-firma, are all plausible explanations for the missing. Who knows of their end except the All Mighty! And He was one who revealed little. Even in our high-tech age with ships suitably robust and fitted with sophisticate sensors and data feeds about the scourges of the sea, they still go missing. “Lost without a trace” often remains the best descriptor.

There are still other factors in the equation of comfort and survival. Most passengers, for example, are people of little or no experience with the sea nor the ways of a ship, and with them came more mouths to feed, more waste, and more to gum things up.

Voyages lasted for months to across the 9,700 kilometers of open ocean, and what had been provisioned, often spoiled quickly; and though animals were carried for food, they too taxed provisions like water and added to the waste stream. Accordingly, the stress on resources was immense and imposed severe limits on rations and one’s freedom of movement about a vessel, and out of this came disease and death. These are just a few of challenges confronting Capitan Quinones and those others heading west.

For a month or so the westward journey had been uneventful for all until the squadron reached the latitudes of the doldrums where they were held in “in irons5.” For five weeks they lay becalmed on a glassy sea, beneath a sky without clouds, and only a mild breeze that ruffled the sails now and then. Soon a fair number of the faithful choose to change course and depart directly onto Heaven.

4

Disease and death had begun to stalk the ships as did the sharks who were alway around. A half month later, and after countless fatalities and prayers, the winds from the East stirred, and once again drove the Spanish fleet westward.

With all this dying and this “trek of closeness” with the members of Church and several hundred others, one might think that the passage would have left something indelible on Capitan Quinones. Well…it did; and though a Catholic, he artfully avoided ecclesial entanglements during the journey through work. There was the on-going disposal of bodies (as quick as possible), the crew’s routine and needs, and that of hundreds of others (the live stock had been eaten by the third week). Fishing from the ship was encouraged, but required close supervision as it frequently led to conflicts; and in two instances, death by falling overboard into presence of the ever persistent sharks, one of which was caught and eaten by the crew.

Despite these hardships, the vessel’s captain, an elderly man and admiral of the fleet, preferred to socialize, eat, sleep, and inspect things, as opposed to sailing a galleon and muddling his mind with the details of navigation.

His kind had become a symptom of Spain’s decline from naval dominance, but fortunately, he had the young Capitan Quinones there to attend to these and other matters. From Quinones’s perspective then, there was little time for churchly matters, lengthy discussions and draw-out sermons over a corpse. From his youth, sermons and the church experience had never resonated with him, and severing in the role as a nominal of commander of the ship, suit him fine. He and the admiral had become fast friends.

It was most fortunate that his father had taught him well in the skills of not only being a forceful man most of the time, “a commander-like persona,” but one who is most persuasive and amiable with his words.

“Your intent is to have others settle upon your preferred options.” It worked well for Quinones, and when cornered, as it would happen now and then, he would kindly remind the offending soul of his— Quinones’s—great burdens, and in the greatest of detail.

Once word of this spread, he was seen by the brethren as, “God’s Jediaha of the Sea, …the warrior who must be left to his work!”

Capitan Alfonso Bernardo Quinones arrived in the Philippines at the age of thirty-two in 1650 as a Spanish navel officer. Once there, and after a year or so of bureaucratic idleness, he convinced himself and his superiors that he would be of “greater value” if he were allowed to resigned his commission and purse commercial objectives in their interest and that of Spain. Resigned he did–in a fortnight and in good

standing–whereupon he launched a lucrative career that benefitted the Crown, as well as the local authorities, and himself. It also allowed Alfonso to make the most of his ship building knowledge and his talent for organization, enterprise, and the love of a good fight.

So now at age of 33, Capitan Quinones had morphed into the merchant-captain role as “Señor Alfonso Bernardo Quinones el Capitan.” No sooner had he freed himself of the navy than he undertook the construction of six ships with his close comrade and

partner Johan Van der Veur. With these vessels, he and Johan would ply the Asian waters as far north as China, and at times, west of the Malayan Peninsula for the region’s riches and sometimes booty. His partner Johan Van der Veur, was an American-born Dutchman. He like Quinones, was literate and was regarded in his homeland of Holland as, “A traitor of the worst sort!”

5

He traded and smuggled with Quinones up to the 1644, then fled northern Europe at Quinones’s encouragement and arrived in Philippines waters in 1651.

By the fall of 1653 Quinones and Johan had completed and launched all of their vessels. Their ships did not conform to the traditions of the Spanish galleons, which had lagged markably by the 1600’s. The majority of the Crown’s ships retained the elevated profiles. They were bulky, top-heavy ships, laden with cannons up high. They carried burdensome and baggy sails accompanied by complicated rigging, which made them slow and difficult to maneuver, particularly in heavy seas. These and other encumbrances were the legacy of the past, an era of sea-warfare where the European ships had become “floating siege castles,” hence the origin of the nautical term forecastle6”.

It was the northern European maritime practices (particularly those of the fishermen) that came into play in their designs, as did one other nautical first for the Old World, the Chines innovation of bulkheads7, which divided a hull into semi-water-tight spaces and strengthened it. Consequently, their ships, both large and small, were easier to handle in the narrows of inter-island passages, and safer if run aground and holed. Their ships were also faster and more seaworthy, and below the water-line all were sealed with the sap of the Palaquium gutta percha tree found in Malaya. It’s worth noting that gutta-percha would be employed by the emerging industrial powers to seal their underwater telegraph cables in the late 1800’s, some 200 years in the future.

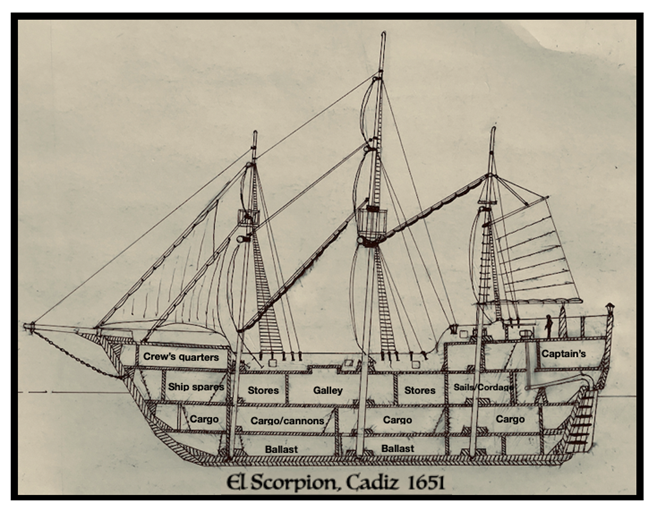

Display 1-3 is a cut-away profile of the Johan’s ship, the El Scorpion, taken from his Colonial Notes of 1682. It and her sister, the Nuestra de La Cruz (Quinones’s ship) were the two largest of their fleet. Notable are their low profiles, raked masts, the absence of castle-like structures forward and aft, like those of traditional galleons, and the elimination of the spritsail8: a square sail9 suspended from a ship’s bowsprit10, and an unnatural death-trap for many. Instead of one large staysail11, they employed two or more smaller ones forward, two main staysails, and one mizzenmast staysail (all are triangular shaped sails strung diangularly forward of each mast. Two are shown furled in Display 1-3. Similarly, they employed more, smaller and lighter square sails. Unlike the square sails of the time, theirs’ differed in that they were configured to be flat and tight when filled with the wind. Moreover, the fabric was internally strengthened with fibers of the batunga vine (several times stronger than hemp); hence their sails fared well in heavy winds. Most innovative was the aft-most trapezoidal sail, the gaff sail rigged on the mizzen mast, which was partitioned Chines-style.

Like their brethren, their four smaller vessels were equally innovative. They were rigged to exploit the trade opportunities in the narrowest of passages and island inlets. Sleek, simple vessels, they retained the use of oars (when needed) for power within shallows and in windless conditions, as well as, a means of quick escapes when necessary. Finally, all of their ships were extensively supplied with small arms of all sorts and fitted with bronze, Chines crafted cannons of superior range.

These innovations and the fact that their ship’s hulls were fashioned of teak and their cordage for their rigging also fabricated from the fiber of the batunga vine, gave El Scorpion and Nuestra de La Cruz formable capabilities for trans-Pacific passages and in the capricious waters of South

6

Display 1-3: Capitan Van der Veur’s original ink sketch taken from his colonial notes of 1682. Capitan Quinones’s Nuestra de La Cruz is the sister ship of the El Scorpion.

China Sea. Their vessels set a standard that has apparently eluded the maritime scholars of Spain’s operations in the East Indies, but were recorded by Johan in his logs and colonial notes.

It was with these ships that Quinones and Johan fed Spain’s lust for the treasures and other goods to nourish the realm’s economy. They would return eastward with cargos of spices hoarded by the Dutch, tropical woods never seen before in Europe, gold bars and nuggets of platinum (not identified as a unique element until centuries later), bolts of beautifully dyed silks, china of exquisite craftsmanship, and cut and uncut gemstones of all varieties (rubies, garnets, safaris, diamonds) and more from the kingdoms of Indian, Ceylon, and the wilds of what is now Myanmar.

As one might expect, Capitan Quinones was a favorite of the Crown. For he, Johan and their crews, the greatest profits naturally followed the successful conclusion of trans-Pacific voyages and the landing of their cargos in Mexico. Profits beyond measure were earned according to Capitan Johan Van der Veur’s colonial notes. The two captains were held in high regard by King Philip IV and, of course, …Olivares, despite Johan’s Dutch origins.

7

Upon his and Johan’s return to the Spanish East Indies, Mexican silver (coveted by the Chinese), tools and weapons, and ship related materials were their cargos. On average, he and Johan crossed the Pacific every three years. Most of their Manila peers were little match for the two. The latter had become technically stagnant, preferring older ship designs that lacked the capabilities for extend voyages, preferring to sell their most valuable cargos to Quinones and Johan, or other Spanish ships heading east. Equally critical, many of the merchant captains were less seasoned in the ways of deep-ocean transits. Rarely were they allowed to join Quinones and Van der Veur on adventures in Asian waters because of this, and a further encumbrance, the scant attention these merchant captains paid to language, diplomatic, and networking skills. Added it all up, the geographic reach of their counterparts was limited, and thus the best and richest cargos generally eluded them. But by 17th century standards, these Spanish entrepreneurs lived well: they held a reasonable social rank in Manila. Food, drink, shelter and women were abundant, and equally important was the distance from the Church and the Crown. And, they had the freedom to set-sail at will with little interference from authorities. There were the obligations of course, like port fees and the occasional tidings called for to fund official affairs.

Not all was smooth sailing for some. There was one note worthy character who cheated. A fugitive Spanish noble (now deceased) defrauded the port’s respected Chinese merchant who dealt in finely crafted sails and precious stones. He, one Señor Yong Lee Qua, did not miss Señor Federico Ruiz who fill to the Dutch. Always looking for a fight with profits in mind, they raided Cavite, and as a result, Ruiz was killed to everyone’s relief.

Despite the wealth they brought to Cavite, the merchant captains were not above making themselves an irritant to Crown’s governor, Viceroy de Manila Señor Vasquez. Such was the case during Quinones’s time. Several of the merchant-captains were overtly tyrannical, and when opportunity beckoned, they were not above nefarious behavior in their dealings with the locals. These scoundrels, in several ”Dutch-like” instances, committed out-right acts of thievery and brutality. These were neither forgotten, nor forgiven, and normally met with retribution.

Though seen as primitive by the standards of the Spanish, the locals were far more astute and crafty, and not given to the likes of cruelty. But some were reputed collectors heads like their Dyak cousins to the West on the Isle of Sulawesi and those tribes of the Salomons to the South. In one instance, famous at the time of course, a large, brutish individual of mixed origins (mostly Scottish), raped and killed a chief’s daughter on his trading mission to the Isle of Cebu. He was subsequently kidnapped (ninja style) from his Cavite quarters and wasn’t found for days. A search of the port’s out-skirts eventually locate the man, or what was left of him. He was found hanging naked

by his heals, beheaded, exsanguinated, and gutted like a pig ready for roasting. Flies smothered the corpse, and not surprisingly, the head was never found. However, the message was clear; and on the whole, the incident somewhat tempered the behavior of those Spaniards inclined to mistreat others. Though grisly, the man’s end was not much of a persuasion to the Dutch who regularly abused the Asians of the Indies for hundreds of years to come.

Quinones, who was not inclined towards passivity, went public on the matter, and in so many words, explained to all, that “the man was, indeed, a true scoundrel at heart, …not a man of God, and was a detriment to their interests and that of the Crown.” He was also quoted as saying, “He had brought it upon himself.” Capitan Quinones’s boldness was judged to be objective and fair by all accounts.

8

At six foot one, broad-shouldered with deep-set dark eyes, Quinones’s persona was indeed commanding as his father had hoped, and this mostly not out of intimidation (except when required), but through listening and discussion. His out-spoken love of sailing, trading and song made him a favorite in Cavite, and when in the company of his most trusted peers, women became the sole topic of interest. His deep, baritone voice added to his charisma, which carried well with the crowds and the ladies.

Nonetheless, his incessant focus on ships and sailing did defer many, particularly those bent on status and ecclesial conversations, but not the other captains and sailors. The topics of commerce, sailing and women held sway above all. The agents of trade and money who were always about, were viewed as a “crafty lot” to be watched and kept at arms length: that is…generally excluded. But they too admired Quinones as they knew him to be strewed and fair in his dealings, and at times, generous; but not one to cross.

Once in the Philippines and despite the incursion into nearly all aspects of one’s life, Capitan Quinones did not take to the Catholic masses with any regularity, and for good reason. And yet, he and Johan were tactfully generous with the Church, providing funds for infrastructure-type needs when called upon. Judiciously they kept to their ships and Cavite’s less desirable warehouse district when not at sea or aboard the de La Cruz. To the clergy, the district as a whole was foul and infested with sinners, and naturally a place to be avoided and safe for the likes of Johan and Quinones. Manila’s elite acknowledged Capitan Quinones’s generosity, but the archbishop remained reticent and regarded him as another womanizer of rank: a man, like so many of Spain’s Grandee class, that when set free in the Crown’s colony, they became distant from the strictures of the Church and quickly fill to the ways of the flesh and lust.

The native women of the Philippines had a special allure that tended to support this claim. It was said that their softness was difficult to resist as it stood in mark contrast to the harshness and the filth of Europeans, were bathing was an infrequent practice at best and one lost in Iberia after the Spanish Christians crushed the Moorish culture.

Though generous, a resentment festered beneath Quinones’s outward charm with good reason. He could not forgive. And who would?. The Church had murdered his great-grandmother and her two sisters for practicing what the Inquisitors determined were “Jewish customs and and Moorish behaviors,” like washing laundry on the Saturday and bathing. They and other family members had perished in the fire storm of Inquisition that swept back-and-forth across the Spanish world; and for Alfonso Bernardo Quinones, it was a sound reason to be a seafarer, fare away in the Spanish East Indies, …out of harms way.

He thus found a sanctuary, and in this, he marshaled his talents which saved him numerous times. There was “an almost disastrous” encounter with a Portuguese man-of-war who’s commander felt that he had the Spaniard corned in a narrow inlet without a means of escape. Capitan Quinones thought and acted otherwise. He shot-up his opponent from a distance until the winds arose, then out sailed their crippled, sluggish monster to safety, only to swing about and lob more ordinance upon the Portuguese from a safe distance with plenty of sea room.

His worst altercation was a prolonged one with a fleet of Chinese bandits off the southeast coast of what is now Taiwan. The ruckus called for aggressive tactics, and Quinones came-on strong from the beginning as the junks closed in on him—in-mass. He charged them with cannon’s blazing, accompanied by fusillades musket-fire, …both accurate.

The junks mistakenly clustered under the maelstrom causing some to collied with one another in seas which were rough at the time. This played to Quinones’s advantage as it allowed him to work the conflict from windward of them. Being stout, stable, and nimble, the de La Cruz provided the ideal platform from which to fire. Four junks were de-masted immediately and severely holed. Five others were set ablaze with fire bombs

9

The battle went on for several hours or more until Quinones took his leave under the push of a rising gale which spread the fires among others in close quarters with those already ablaze. According to his crew’s accounts, “…it was a storm of fire, …with many giving way to the depths.” As told earlier, the discipline and training of Quinones’s crew’s paid-off. He logged that eleven junks eventually sank.

Despite these encounters, Quinones managed safe passages, for the most part, into dangerous waters that others in his line of work avoided. In doing so, and regardless of his allegiance to the Crown and the support of local authorities, he effectively avoided Spain’s conflicts with the other regional powers such as the Dutch VOC, the Portuguese, except for that one encounter, and the infrequent British interlopers who would eventually came to rule the Indian subcontinent, southeast Asia and destroy the Chinese kingdom with their opium drug trade.

Though less apparent in the historical records was his predations on those VOC privateers in the waters between the Dutch held territories and those of Spain. He regularly sought them out, and stripped them of their weapons and valuables, and their ships of their cargos, sails and rigging. Many were left adrift until rescued by either their brethren or those native groups who relished the flesh and skulls of the whites. To this day, the remains of many of those unfortunates still adorned the long houses of the native descendants who regard such relics as a measure of theirs’ ancestors prowess in the confronting the likes of the white man.

Quinones’s and Van der Veur’s preferences were for the peoples of Asian decent; and it is in this sphere, that their skills with the spoken word–the language of others–gained respect and the best of the wealth that Spain coveted, particularly spices from those Dutch traders operating independently of the VOC and seeking Spanish silver in kind. This he and Van der Veur could provide in return for nutmeg, pepper, cloves and cinnamon along with a good measure of respect and benevolent behavior. These spices and the gem stones were their cargos loaded for New Spain and the trans-Pacific voyage the 26th of April, 1667